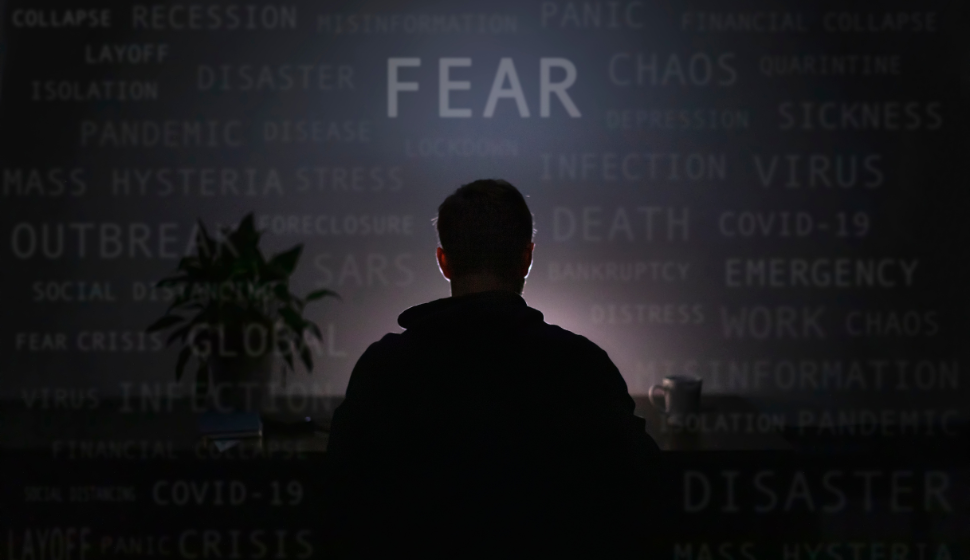

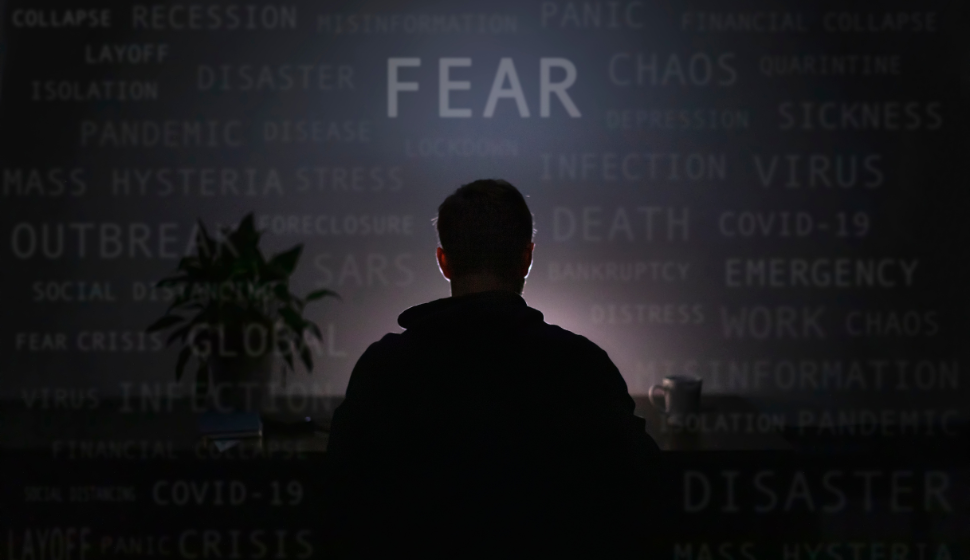

Fear

For a very long time, we have known from studies that human nature would almost require us to do anything that we think might protect us from real, imagined or clearly perceived dangers. The other side of that is that, out of a desire for the preservation of organized society, we are under the requirement of law that precludes us from responding to fear in any extreme way unless our lives are inarguably threatened. Since authority determines the rules of society, authority also decides who is eligible to respond to fear, even in an extreme way, and who isn’t.

Authority sets up structures to determine what response is appropriate and what response is not. Therefore, a member of a dominant group may not be subjected to the same expectations and/or consequences as a member of a marginalized group even if both individuals respond to fear in the same way. To this end, the stories of the trials of George Zimmerman in the murder of Trayvon Martin and Marissa Alexander in her trial for firing a warning shot in the direction of her abusive husband – under the same “Stand Your Ground” law in the same state of Florida and the same prosecutorial district – is very instructive. While Zimmerman who killed Trayvon Martin walked out of court a free man, Alexander who caused no injury to her abusive spouse received a 20-year jail term. The only distinguishing factor in both cases was that both Mr. Trayvon Martin and Ms. Alexander were members of a group that is deemed appropriate to be described as “other” in the eyes of our law.

In contemporary society, authority figures are increasingly making an art of defining the objects that people should fear. Despite the fear that we may feel, we must submit to the powers that sanction our ability to respond to fear, and determine how we respond. Having submitted, authority also expects us to accept their choice of language that they will use to initiate, maintain, and increase our fear even as they tell us that they exist to protect us from the objects of our fear. As if that is not enough, they define the objects of our fear. For the current government in the United States, the language and objects of fear that they have chosen for us include such terms as “law and order”, “bad dudes”, “refugees”, “extreme vetting”, “terrorists”, “Islamic extremists”, “Jihadists”, “Muslims”, “criminals” and “illegals”. Around the world, immigrants, political opponents and members of minority groups have been the chosen objects of fear.

In South Africa, the objects of fear that must not only be illegally arrested or harassed but also killed are black immigrants from other African countries. While people who follow developments in South Africa may perceive of this as somewhat of a deviation from the argument thus far in the sense that the South African government did not choose the objects of fear now being killed on South African streets, it is by no means a deviation. The reality is that by condoning the actions of the killers and publicly making statements that range from denial to implicit support for the killers to toothless bravado, that government by its complicity has chosen the current victim groups as the objects that the people should fear. But the case of South Africa is by no means unique in this regard, even if the difference may be of kind rather than degree – depending on whose perceptions are being expressed. Certainly, the current South African situation exposes the emptiness and extreme weakness of the judicial, social, and political institutions of a corrupt nation on the one hand and, on the other hand, the penchant of frustrated and downtrodden thugs for jungle justice.

Around the world, immigrants and members of minority racial and ethnic groups are marginalized and, yet, are the objects that society is encouraged to fear. To call this thinking illogical is to understate the degree of senselessness inherent both in the conception and practice of otherism.